Abstract

India’s fertilizer industry has transformed, ensuring food security for over half a century. Despite challenges like geopolitical tensions and climate change, innovations and policy support drive sustainable agricultural growth.

Introduction

Unlike other periods in contemporary Indian history there has been no famine in India during the past half a century. Agricultural production witnessed a steady increase from the 1970’s to the present (2023), which now stands at 329.7 million tons of grain production. In India, several factors contributed to this big achievement, the foremost among them being the use of mineral fertilizers in the farmlands. Globally, India is the second largest producer and consumer of fertilizers only after China.

As of now, the fertilizer manufacturing industry in India is a robust venture, utilization of installed capacities is good and the profitability of the business is also better. The situation was different just five years back when government subsidy was inadequate and that too not available to the manufacturing units in time resulting in heavy financial strains to maintain operations of the unit. Some major players left the scene as they found other investment options more lucrative.

Domestic Production

Urea, DAP, NP and NPK complex fertilizers, ammonium sulphate, potash and single super phosphate (SSP) are the major fertilizer products used in Indian agriculture. India has a high dependency on imported fertilizer raw materials, intermediate and products.

Table 1: Installed capacity and production of fertilizers

In India, farming and the production of food grains is not a big-ticket business being operated at industry level. Though there are large farm holdings owned by some houses, the bulk of the Indian farmers are small and marginal ones who cultivate for subsistence and sell surplus to the market. Therefore, there is a heavy dependence on government support system, which are available in the form of fertilizer subsidies and minimum support price for procurement of grain by the agencies in the government.

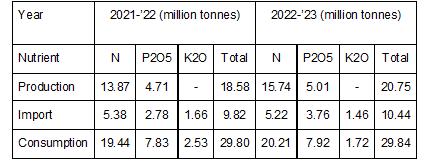

Table 2: Production, import and consumption of fertilizers

Food fertilizer and fuel subsidies constitute a big junk of government finances in the budgets presented to the Parliament every year. Following the Ukraine war and development of a troubled geo-political situation in the Middle East; there has been a complete disruption in the supply chain in the fertilizer industry.in the government from time to time and thus the government still has a say in fixing the prices of complex and potassic fertilizers.

Import of Fertilizers

The highest import dependence is for potash for which no domestic sources are available. Efforts are underway to recover potash from spent lye from the sugar industry and from seawater bittern. In the case of phosphatic fertilizers for which raw material (phosphate rock), intermediate (phosphoric acid) and finished products (DAP and NPK complex fertilizers) need to be imported from other countries. Available phosphate deposits in Jhamarkotra in Rajasthan contain only a lower P2O5 content suitable for making SSP only. Around 30% of the country’s urea requirement is met by imports. Every year the government earmarks a sizable quantum of foreign exchange for the above imports.

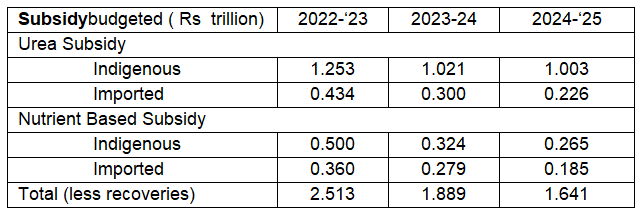

Fertilizer Subsidy

Under the Indian fertilizer subsidy regime, producers are asked to sell fertilizer materials (especially urea under the Retention Pricing Scheme – RPS) to the farmers at a price fixed by the government that is affordable to them. The price differential between cost of production together with a reasonable return on investment and the market realisation for every ton of product dispatched from the plants is paid to the manufacturer as a fertilizer subsidy. Urea is the largest volume fertilizer consumed in India and it comes under the subsidy regime.

Phosphate, complex and potash fertilizers have been partly decontrolled from pricing in 1992 and placed under a nutrient based subsidy (NBS) scheme since 2010. A fixed subsidy amount depending on its nutrient content (N, P, K, and S) is allowed for these products. It is revised by the Department of Fertilizers in the government from time to time and thus the government still has a say in fixing the prices of complex and potassic fertilizers.

Following the shift in the geopolitical situationi n Europe the cost of domestic production increased heavily and so also the subsidy burden on the government. To sustain production, the government absorbed all price rice and thus during 2022-23 the subsidy bill went as high as 2.51 trillion rupees.

Table 3: Fertilizer subsidies

Nutrient Efficiency

Even though per hectare consumption of fertilizer nutrients in India is much lower than compared to Japan, China, Egypt, Korea etc., the fertilizer use is still lower. Serious efforts were made to scientifically analyse the nutrient demand of the soil and administer the requisite quantum of nutrients to the crops. The government has issued soil health cards to farmers to promote integrated nutrient management for improving soil fertility and increase productivity.Farmers are advised to use a judicial mix of chemical, organic, bio fertilisers and other innovative fertilisers as recommended by the soil health card. Together with fertigation, drip irrigation, proactive soil nutrient and water management, the fertilizer use efficiency is being improved and wastage of valuable crop inputs is reduced to some extent.

Farmers are also encouraged to use coated, modified, and fortified fertilizer materials for better nutrient administration and to reduce pollution from leaching of nutrients to the environment. Thrust was also given to the use of secondary and micronutrients. Water soluble fertilizers (WSFs) are also produced and marketed by several producers. It dissolves completely in water and the nutrients are more efficiently absorbed by the plant through fertigation. Additional subsidy is provided under the NBS scheme for fertilizers fortified with boron and zinc.

Nano Urea and DAP

A major turning point in the Indian fertilizer sector is the development of Nano urea and DAP by agriculture scientists. These are nano technology products in liquid form which can be used as foliar spray for top-dressing instead of conventional soil based application of urea and DAP. The country’s major fertilizer producer in the cooperative sector IFFCO started industry scale manufacturing of the nano-products and that is made available to the farmers. Initial results indicate promising gains from the foliar application of nano-products to the crops and its long term implications are being studied.

Being an agrarian country India has a large reserve of biomass. Use of biomass for fertilizer application is being promoted in a big way. Composted municipal waste is also being used widely by Indian farmers. Of late, gasification of biomass to produce ammonia is also being explored by manufacturers.

Decarbonization of the Industry

The fertilizer Industry is both energy and carbon intensive. The carbon intensity has substantially reduced from the shift in the feedstock from coal and liquid petroleum components to natural gas. The Indian industry is highly optimized on the energy consumption front over the years incorporating the developments in unit operations, energy conservation, waste reduction, reactor revamp technologies, use of innovative equipment and catalysts and improving overall plant safety.

Most of the Indian plants are of vintage prior to 1995 except a few. A good number of retrofits and revamps have taken place in each of these plants as part of modernization, energy conservation and efforts to better safety and environmental aspects. In the present context of advancing decarbonisation, existing operators may have to adopt carbon capture sequestration and storage (CCSS) or other technologies to fall in line with the national agenda towards net zero emissions.

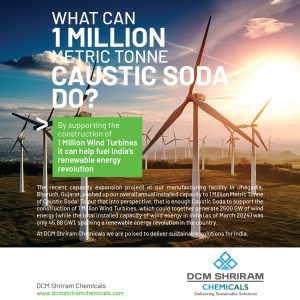

In the coming years, water electrolysis using rene-wable power to produce green hydrogen is slated to become the technology for ammonia synthesis. India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM), National Solar Mission, National Bioenergy program, Ministry of Renewable Energy and Bureau of Energy Efficiency are partners in this pioneering program.

Already serious carbon reduction programs are being taken up by the world’s most renowned fertilizer producers across the globe and the Indian industry has also to fall in line with the above to ward off the adverse impacts of climate change.

Outlook for Future

Fertilizer is a strategic input to agriculture and therefore it is still one of the prime considerations of the government. The industry which was mostly a public sector activity in the 1980s is now dominated by the private sector due to change in the Government of India’s public policy towards state owned industries. The Government of India has made serious attempts to disinvest the public sector fertilizer units but so far not succeeded. Of late, the disinvestment of the public sector fertilizer units is not a priority item before the Government. Decarbonization of the industry to produce green fertilizers will certainly add on to the cost of production which can be overcome by diligent application based on the 4R concept (right source, right rate, right time, and right place) and by increasing nutrient efficiencies.

The Indian population now stands at 1430 million in 2023 and is growing at the rate of 0.92 % per annum. Around 68% of the people belong to a working age group and thus India is a young nation. The food demand is going to increase in the coming years and therefore a stable policy for sustainable agriculture duly supported by optimized production, effective delivery and utmost diligence in its use efficiency are important for the country.