Amidst the growing culture of automation, our columnist plays Devil’s Advocate by drawing upon his personal experiences from the last 4 decades. While AI and automation will improve efficiency, the same cannot be said unequivocally about safety. People are at the centre of process safety and human oversight should not be done away with.

As the pandemic continues to persist, businesses that are on the right side of the digital divide are appearing to be doing better. This is hastening the adoption of automation in many businesses and industries. There is a growing narrative that automation will improve safety. I wish to offer a counter-narrative by digging deep into my diaries.

Ear to Pipe

It was the summer of 1982. I can vividly recall my first plant startup. The plant was in Punjab, located right in the middle of ripening wheat-fields, not too far from the country’s then biggest hydroelectric power project. One of the many process steps in the plant involved bubbling carbon dioxide through 4 reactors arranged in parallel. The gas had to be more or less evenly distributed among the 4 reactors and there were no flowmeters. The one-man process licensor was a wizened gentleman, probably in his 70s. I was amused to watch him put his ear to the distribution pipes and adjust the valves. But it worked perfectly! There was no control room in the way we understand now and I spent all of my time in the plant, observing – watching, listening, touching – through my senses.

Graveyard Shift

Fast-forwarding 5 years, Single Loop Controllers and chart recorders were the rage in the industry. It was my second plant startup and I was supervising the night shift. The steam to hydrocarbon ratio was the most critical parameter in the steam reforming process. Sometime between 2 and 3 in the morning, when the alertness level is the lowest, a gasket in the steam line gave away. As the steam leak increased over the next few minutes, the flow meter located upstream of the leak sensed the rise in flow and started closing the control valve. As the leak continued to increase, the control valve went fully shut cutting off steam to the process. The chart recorder in the control room showed a perfectly healthy straight line. But all the steam that was being measured was leaking out and not entering the process. If only the field operator had been alert enough in the dead of the night! The carbon deposition over the catalyst was brutal. The coke had to be drilled out of the reformer tubes.

Alarm Overload

Fast-forward another 5 years. It was the age of DCS. The PSU client was setting up a plant whose technology they were not familiar with. We had a very comprehensive Hazop Study spread over a month at 2 different locations. It was a large team, consisting of as many

as a dozen specialists from the client’s side. There were numerous recommendations; many of them pertained to adding alarms. An additional alarm tag did not add to the project cost as it was on DCS. 18 months later, after the plant had been successfully started up, the client urgently summoned me to the plant. Too many alarms were buzzing and distracting the operator. Over that week, we reviewed each and every alarm and downgraded many of them, even eliminating a few. Such “alarm rationalization” studies have now become the norm in the industry.

Ghost in the Machine

Let me now leap into the first decade of the new millennium. We were controlling an important sequence through a tried and tested logic. The logic had been perfected over one full decade in several plants. It was also comprehensively tested in a FAT at the vendor’s

works. But yet, the unthinkable happened one day. It malfunctioned n an entirely inexplicable way. There was a mysterious ghost inside the software. It caused considerable

downtime. It also rocked my faith in automation.

Safety Culture

In March 2005, an explosion in the BP Texas City Refinery killed 15 and injured 180 besides causing considerable damage to assets and loss of production. It is one of the most widely studied accidents of the chemical industry and is routinely taught in the undergraduate curriculum on process safety. The incident occurred when a distillation column got overfilled during start-up and hot inflammable material spilled out. The apparent cause was the failure of level instruments that failed to alert the operators to the imminent danger. Yet, the 341-page report issued by the US Chemical Safety Board (CSB) attributed it squarely to management failure. The refinery did not have a safe blowdown system to face the kind of scenario that presented itself on that fateful day in March. BP’s cost-cutting measures prevented them from investing in plant modernization. The plant was also seriously understaffed. The report went on to castigate BP management for their poor safety culture. BP accepted the conclusions and recommendations of CSB in total.

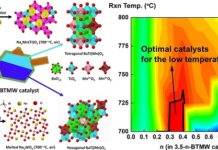

Layers of Protection

The touchstone of safety in the chemical industry is the famous 9 “Layers of Protection”. he innermost core is the inherent safety built around 4 principles of Minimise, Substitute, Moderate, and Simplify. The 3 layers of protection ascribed to control and instrumentation are sandwiched between the inner core of inherent safety and 5 outer layers of physical protection (relief devices and bunds) and emergency response systems. The instrumented layers are always vulnerable to failure, either accidentally or intentionally. The focus should thus be on strengthening the inner core and making the outer layers more robust.

Age of Automation

Automation is the central column around which the nine pillars of Industry 4.0 are constructed. Sensors and transmitters have become exceedingly smart. Connectivity speeds are lightning fast. Inanimate objects can communicate with each other without human intervention. Supercomputers fitted with AI-based algorithms can outthink us and come up with ingenuous solutions to challenging problems. Will the chemical plant operation be taken over by robots and AI? The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed and disrupted things in unimaginable ways. The unthinkable of yesterday is very much in

the realm of possibility today. The chemical industry cannot be immune to the tsunami of change that is sweeping across the world.

Epilogue

Will automation improve safety in the chemical industry is a moot point. The case for deploying robots has never been more attractive in the wake of the pandemic. They will neither fall sick nor get tired. But surrendering human oversight may not be prudent.

We are already familiar with how airlines and banks are brought to their knees when systems develop glitches. Humans are unable to perform tasks that they were comfortable

doing just the other day. An ever-increasing reliance on computers has already dulled many of our skills like memory, visualization, and mental arithmetic. Automation should not atrophy our minds and safety culture.

Readers’ responses may be sent to:

k.sahasranaman@gmail.com or

chemindigest@gmail.com