In 1900, a bright 23-year-old British chemist with a First-Class Honours degree in chemistry and two years of independent research at Oxford University under his belt was eager to begin life as an academic. But, he was sorely disappointed when no suitable job offers came his way. Learning of an opening at the University of Toronto on the retirement of the chemistry professor, he applied for the position and sailed to Canada for a personal interview. He failed to get the job. That young man’s name was Frederick Soddy.

Continuing his job search in Montreal, he was appointed to a much lower post as laboratory demonstrator at McGill University. This led to a historic alliance with the 29-year-old junior physics professor there – Ernest Rutherford. Their research revealing that radioactivity occurs when one element naturally changes into another, not only stunned the chemistry world but resulted in Soddy adding the word ‘isotope’ to the English dictionary later on and his work on isotopes winning for him the 1921 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Frederick Soddy was awarded the prize “for his contributions to our knowledge of the chemistry of radioactive substances, and his investigations into the origin an nature of isotopes”.

Early life

Soddy was born on 2 September 1877 in Eastbourne, Sussex, the youngest of seven children of a London merchant. He majored in Chemistry from Merton College, Oxford University in 1898, with another great scientist William Ramsay as his external examiner, moving on to carrying out independent research at the same university for the next two years.

After investigating the emanations of radioactive elements as they decayed into other elements and publishing several papers on radioactivity in collaboration with Ernest Rutherford, Soddy returned to England from Canada in 1903.

For the next year, he worked with his former teacher William Ramsay at University College in London. Based on spectroscopic studies, the two of them proved that helium gas was generated following the radioactive decay of radium. Rutherford who had also studied the emanations from radium had already predicted this as the weight of the alpha particles released by radium approximately matched that of the mass of helium atoms.

Soddy then taught as a lecturer in physical chemistry and radioactivity at the University of Glasgow for ten years (1904-1914), had a brief stint as professor at the University of Aberdeen that was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, and was then appointed as professor of chemistry at Oxford in 1919 where he taught till his retirement in 1937.

Astounded by the implication of their research findings proving that the atoms of a radioactive element changed into those of another element, Soddy had exclaimed, “Rutherford, this is transmutation.” An alarmed Rutherford had retorted, “For Mike’s sake Soddy don’t call it transmutation – they’ll have our heads off as alchemists.”

Significant achievements

At the time when Rutherford and Soddy collaborated on studying radioactive substances, the emanations from such materials had already been identified as alpha, beta, and gamma rays, but very little was known about the phenomenon of radioactivity. Some physicists held the view that previously absorbed energy was being re-emitted without the elements themselves undergoing any fundamental transformation.

Before Soddy joined him in Montreal, Rutherford, as an experienced physicist, had just discovered that thorium, like uranium, constantly gave off some radioactive gas that he had yet to identify. He was even more puzzled on finding that radium and actinium too produced similar emanations. He realised that for chemically separating the products of decay from the original source materials he would need expert chemical assistance. Soddy, a chemist with an excellent understanding of atomic formations, provided the proficient support Rutherford needed.

Astounded by the implication of their research findings proving that the atoms of a radioactive element changed into those of another element, Soddy had exclaimed, “Rutherford, this is transmutation.” An alarmed Rutherford had retorted, “For Mike’s sake Soddy don’t call it transmutation – they’ll have our heads off as alchemists.” And so, when they presented their findings in print, they described the phenomenon they had observed as “spontaneous transformation”. Though their collaboration was brief, lasting just for eighteen months, the Soddy-Rutherford research was extraordinarily fruitful and helped solve many of the puzzles related to radioactive elements.

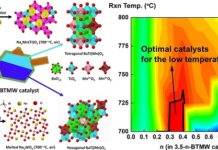

While at the University of Glasgow, where he continued with his chemical work on radioactive materials, Soddy developed what he called the “displacement law” according to which “when an alpha or beta ray is emitted, the element moves to a different place in the periodic table”. Around the same time, the Polish-American physical chemist, Kazimierz Fajans, too discovered this same phenomenon which is known today as the radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy. But Soddy’s most significant work here occurred in 1913 with his formulation of the concept of isotopes, a term derived from the ancient Greek words meaning ‘same place’. He discovered that the atoms of a radioactive element could have different weights, yet have the same chemical properties and occupy the same position in the periodic table. Despite their different weights, he asserted they were not different elements but isotopes of the same element. Some years later, J. J. Thomson showed that non-radioactive elements too can have multiple isotopes.

In the meantime, Soddy also began to become more socialist in his thinking and got involved in adult education, and even delivered several lectures on radiochemistry suggesting that one-day nuclear energy could be a source of abundant, cheap, and clean power, thus solving the problems of pollution and poverty. He however also warned that its uncontrolled release could result in horrific destruction. His lectures were published as a book titled ‘The Interpretation of Radium (1909). Inspired by Soddy’s book, H. G. Wells wrote ‘The World Set Free’ (1914) – a futuristic novel about biplanes dropping atomic bombs during some war in the future and the earth being destroyed by nuclear explosions and radioactive debris. Wells dedicated the book to Soddy. A prolific writer, Soddy authored a number of books some of the most well-known ones being ‘Matter and Energy’ (1912) and ‘The Story of Atomic Energy’ (1949).

In 1920, as a professor at Oxford, Soddy predicted that the rates of radioactive decay being known, isotopes could well be used for finding out the geologic age of rocks and fossils. His words came true a few decades later when Willard Libby developed modern radioactive dating techniques, winning the 1960 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his achievement. Incidentally, Soddy had also rightly predicted that someday a single currency could unite Europe.

Later Life

When Soddy’s wife Winifred was alive, the two of them enjoyed trekking through hills and skiing together. He even supported her in her campaigns for women’s rights. Soon after her sudden death in 1936, he retired from Oxford University.

But even at Oxford, Soddy spent less time on research and radioactivity, taking a keen interest in economic and social issues. His views on these issues were unpopular and controversial but he was outspoken about his thinking and wrote several papers and books on these topics. He emphasised the need for drastically restructuring the global economy. He even wrote about a novel economic theory based on the laws of thermodynamics, arguing that ethics and morality should also be given as much importance as supply and demand in economics.

Around a year before he died on 22 September 1956 at the age of 79, he joined 17 other Nobel Prize winners in appealing to world leaders to give up nuclear weapons.

Soddy also began to become more socialist in his thinking and got involved in adult education, and even delivered several lectures on radiochemistry suggesting that one-day nuclear energy could be a source of abundant, cheap, and clean power, thus solving the problems of pollution and poverty. He however also warned that its uncontrolled release could result in horrific destruction.

Recognitions and awards

Besides the Nobel Prize, Soddy was also the recipient of many other richly deserved honours and awards. In 1910, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Oxford University bestowed an honorary degree on him, and in 1951 he was awarded the Albert Medal. In 1981, Sweden honoured him on a stamp, along with two other 1921 Nobel prize winners who were similarly honoured by being featured on stamps. The two others were Albert Einstein (Physics), and Anatole France (Literature). Also, a crater on the far side of the moon and the radioactive Uranium mineral Soddyite have been named after him.

In line with his personality and humanitarian outlook, and as someone with an interest in social issues and other subjects too in addition to chemistry, Soddy asked that most of his assets be used after his death for establishing a trust fund to help teachers and students visit unfamiliar communities inside and outside Britain. Fritz Paneth, the Austrian-born British chemist after whom the mineral panethite is named, had rightly said this about Soddy: “He was gifted in many ways, perhaps too many ways.”

References

1. Nobelprize.org: Frederick Soddy – Biographical -Nobel Media AB 2014, https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1921/soddy-bio.html

2. Marc A. Shampo Ph.D., Robert A. Kyle, MD, David P. Steensma, MD: Frederick Soddy -Pioneer in Radioactivity – Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Jun 2011; v 86(6)

3. Luisa Bonolis: Frederick Soddy (1877-1956) – Lindau Mediatheque, http://www.mediatheque.lindau-nobel.org/research-profile/laureate-soddy

4. Mike Sutton: Transmutations and isotopes –Chemistry World, 26 April 2006 Elisabeth Ratcliffe: Frederick Soddy – 175 Faces of Chemistry, September 2015, http://www.rsc.org/diversity/175-faces/all-faces/frederick-soddy

5. Norman W. Hunter, Rachel Roach: Frederick Soddy- Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, 1901-1992, James K. Laylin, Editor, American Chemical Society and Chemical Heritage Foundation, 1993.