On November 13, 1930, the announcement for two of that year’s Nobel Prizes was made. The first was the Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to 42-year old Indian physicist Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, Professor of Physics at Calcutta University, for his work on the scattering of light and the discovery of the Raman effect named after him. The second was the Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to 49-year old German chemist Hans Fischer, Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Technical University of Munich, for his research towards discovering the molecular structure of the biological pigment hemin (one of the two components of haemoglobin – the non-protein, iron-containing one) and chlorophyll, and especially for his synthesis of hemin.

One of Germany’s greatest organic chemists, Hans Fischer’s crowning achievement was being honoured as a Nobel Laureate, a fitting reward for the years he devoted to carrying out intensive research on natural pigments and on the chemistry of pyrroles. His work made it possible to synthesise hemin (or haemen) from simpler organic compounds. Fischer’s breakthrough feat was producing a synthetic hemin that was indistinguishable from the natural hemin obtained from haemoglobin.

From Classical Studies to excelling in Organic Chemistry

Hans Fischer was born on 27 July, 1881 in Hoechst on the River Main, a major centre of chemical industries in Germany. His father, Dr. Eugen Fischer, being the Director of a chemicals manufacturing company, he was exposed to the field of chemistry from a very young age. He began his schooling at a primary school in Stuttgart and then completed his matriculation in Wiesbaden at the Humanistische Gymnasium, a reputed humanities-oriented grammar school where children learnt about the Classical Age and the cultural history of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

In 1899, he joined the University of Lausanne, simultaneously commencing studies in chemistry and medicine. He completed his doctorate in chemistry from the University of Marburg in 1904 and got his Doctor of Medicine degree in Munich in 1908, studying under Friedrich von Muller, the renowned physician and clinician. For the next two years, he worked in Berlin as an assistant to the eminent chemist Emil Fischer at the First Berlin Chemical Institute. Emil Fischer had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1902 for his extraordinary work on sugar and purine syntheses. Under his direction, Hans Fischer studied peptides and sugars.

But it was F. von Muller, his former professor and supervisor, who sparked Fischer’s interest in pyrrole pigments by inviting him to work with him at the well-known Second Medical Clinic in Munich in 1910. Under Muller, he began to examine the composition of the bile pigment bilirubin, something he would continue to be engaged in during the decades that followed. He spent a year or so there studying the relationship and similarities between the pigments of blood and bile alongside Muller and other researchers, before working as a lecturer for four years in the same city.

After that, in 1916, he moved to neighbouring Austria on being invited to succeed Adolf Windaus (who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1928) as the Professor of Medical Chemistry at the University of Innsbruck. Delighted by the tranquil beauty of the surrounding Alpine countryside, Fischer enjoyed skiing and mountain climbing here in his free time. He spent two happy years in Innsbruck till tragedy struck unexpectedly while he was out mountain climbing with his father in the Alps. Right before his very eyes, his father died tragically on falling into a deep crevice.

For the next three years, Fischer then held the chair of Medical Chemistry at the University of Vienna before being appointed as Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Technische Hochschule (Technical University) in Munich in 1921, a position he held till his death. In the beginning, many questioned the wisdom of appointing a professor of medicine to a position of responsibility at a technical institute.

But Fischer proved all the people who doubted his capabilities wrong. He successfully set up a big and extremely productive research laboratory well equipped for systematic investigations of all facets of the chemistry of pyrrole, bile pigments, and other related compounds. He also soon became hugely popular with his students and his staff as well. His enthusiasm and commitment to his work inspired a large number of graduate students to work with him as his loyal disciples. They were equally committed to the research projects he had undertaken and were determined to help him accomplish his goals. Fischer trained several students to become brilliant chemists and was instrumental in many of them emerging as industry leaders and distinguished academics in Germany and abroad. And not only was Fischer a great teacher and researcher, he was also an excellent administrator.

Indefatigable researcher, ground-breaking discoveries

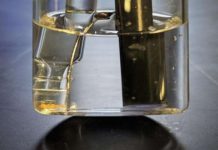

Fischer devoted around three decades of his life to the study of the highly significant biological compounds haemoglobin, chlorophyll, bilirubin, and other bile pigments. In 1921, he began his research work on hemin. At that time, not much work had been done on the synthesis of pyrroles – the molecules that impart colour to different biological substances. The work was time-consuming and laborious and with the help of his large team of microanalysts and doctoral students, he carried out over 60,000 microanalyses in his lab. Finally, he discovered the molecular structure of hemin and showed that it comprised four pyrrole rings linked by bridges, with an atom of iron in the centre. In 1929, he successfully synthesised hemin.

Fischer then began investigating the structure of the chlorophyll molecule and the pyrroles he obtained from the decomposition of chlorophyll. Having only partly succeeded in the difficult task of synthesising chlorophyll, he turned his attention to the bile pigment bilirubin that he had first become acquainted with in Muller’s lab. Till then, though bile pigments had been discovered several decades earlier, hardly anything was known about their chemical composition. After almost a decade of studying the bile pigments, Fischer finally discovered the molecular structures of both, bilirubin, that gives rise to the yellow colour in jaundice sufferers, and biliverdin, that gives a yellowish colour to bruised skin. In 1942, he synthesised biliverdin, and in 1944, he succeeded in the more complex activity of synthesising bilirubin, thus completing the work Muller had begun.

Fischer authored over 300 research papers, most of which were published in the scientific journals Liebigs Annalen der Chemie and Hoppe-Seylers Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie. His work paved the way for further research on natural pigments. With two of his colleagues, he also co-authored three volumes of a major work on pyrrole chemistry – Die Chemie des Pyrrols (The Chemistry of Pyrroles).

Acknowledgments

In recognition of his extensive scientific work in the field of natural pyrrole pigments, the title of Privy Councillor (Geheimrat Regierungsrat) was conferred on Fischer in 1925. He was awarded the Liebig Memorial Medal in 1929, the Nobel Prize in 1930, and the Davy Medal in 1937. In 1936, Harvard University honoured him by conferring an honorary doctorate on him. The lunar crater Fischer is named after both Hans Fischer and Emil Fischer. The Technical University of Munich holds the Hans-Fischer Symposium in his honour in November each year in the Hans-Fischer Lecture Hall of the Chemistry Department.

Completely dedicated to his work, Hans Fischer married rather late in life, when in his fifties. He and his wife Wiltrud didn’t have any children. He however continued to be an avid lover of mountain climbing and skiing. Suffering from serious ‘surgical tuberculosis’ when he was younger didn’t deter him from fearlessly engaging in strenuous outdoor activities. Sadly, he was so devasted when the renowned laboratory he had set up and almost all his life’s work was destroyed during the bombing of Munich towards the close of World War II that he took his own life by committing suicide at the age of 63 on Easter Sunday, 31 March, 1945.

Incidentally, Emil Fischer, the celebrated Nobel Laureate he had briefly trained under, was also believed to have ended his own life. He had suffered from spells of depression due to personal tragedies – his wife died just seven years after they got married, and two of his three sons died in their twenties during World War I. He is thought to have killed himself in 1919, finally overcome by depression after being diagnosed with terminal intestinal cancer.

Notwithstanding their tragic ends, both Emil Fischer and Hans Fischer have left behind a glorious legacy and are shining luminaries in the long line-up of outstanding German chemists.

References

- NobelPrize.org: Hans Fischer – Biographical – Nobel Media AB 2014, https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1930/fischer-bio.html

- YourDictionary: Hans Fischer – http://biography.yourdictionary.com/hans-fischer

- Soylent Communications: Hans Fischer – http://www.nndb.com/people/376/000100076/

- Adolf J. Stern: Hans Fischer (1881–1945) – Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 206: 752-761, October 1973, https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb43252.x

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Hans Fischer German Biochemist – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hans-Fischer

- Encyclopaedia of world biography: Hans Fischer – https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/history/historians-miscellaneous-biographies/hans-fischer

- Zexia Barnes: 1930 Nobel Laureate Hans Fischer – Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, 1901-1992, James K. Laylin, Editor, Chemical Heritage Foundation, 1993.