When Irène Joliot-Curie and her husband Frédéric were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 “in recognition of their synthesis of new radioactive elements”, Irène created Nobel history of sorts. She became the only Nobel Prize awardee in any discipline whose parents (Marie and Pierre Curie in her case) and husband were also Nobel Laureates. Not to mention that the Curies have the most number of Nobel Prizes than any other family in world history.

Carrying on the legacy of scientific work, both Irène Joliot-Curie’s children went on to excel in the scientific field, her daughter Hélène becoming a renowned physicist and son, Pierre growing up to be a noted biologist.

Moreover, like her illustrious parents, Irène and her husband Frédéric were not just life partners, they were successful lab partners as well, emerging as the first to discover artificial radioactivity by synthesizing radioactive elements in the laboratory. The elements they discovered are being used till today to save millions of lives worldwide.

Actually, Irène and Frédéric narrowly missed winning the Nobel Prize on two earlier occasions. During their initial experiments, they had identified both the positron – the antimatter counterpart of the electron, and the neutron – the missing particle of atomic nuclei whose existence Rutherford had predicted in the early 1920s. Unfortunately, they did not interpret their research results correctly and failed to catch on to the implications of what they had discovered. Later, James Chadwick was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935 for his discovery of the neutron in 1932, and Carl David Anderson who discovered the positron in 1932 won the Nobel prize in Physics in 1936.

The positive fallout of these near misses, however, was that their further research led them to discover manmade radioactivity and be honoured with a Nobel Prize in Chemistry, though unfortunately, this recognition came a year after Marie Curie had passed away.

Growing up influenced by science

Irène Curie was born on 12 September 1897 in Paris after Marie went into labour one month before time following an exhausting bicycle ride she and Pierre had taken into the countryside. When her father Pierre met with a sudden tragic accident, Irène was just eight years old. A few years later, she lost her beloved grandpa, Dr. Eugène Curie, who had introduced her to the sciences and also taught her to love nature, poetry, and radical politics.

Less than three years after Pierre’s untimely death in 1906, disappointed by the existing education system in Paris, Marie joined hands with a few of her academic colleagues at the Sorbonne to set up a unique schooling arrangement for their children called ‘The Cooperative’. In this special school, each of the academics taught the children, a group of ten including Irène, in their own homes. That was how the young Irène came to be educated by eminent scientists and scholars. She was taught physics by Marie Curie, chemistry by Jean Baptiste Perrin who was later awarded a Nobel Prize in physics, and mathematics by the renowned physicist Paul Langevin.

Though the informal school was dissolved within two years, it had a deep impact on Irène. Besides, Marie made sure that Irène and her younger daughter Ève (who later became a well-known pianist and journalist) were physically strong and exercised regularly at home. She also encouraged them to engage in horse riding, hiking, swimming, skiing, and gymnastics.

In 1911, the 14-year-old Irène accompanied her mother to Stockholm, Sweden to watch her being honoured with her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry. She resumed and completed her schooling in Paris in a regular school and then in 1914, at the age of 17, she joined the Faculty of Science at the Sorbonne for college studies which were interrupted by the breaking out of World War I that same year.

Though still a teenager, she took up a nursing course even as she continued with her college studies, and then served as a nurse radiographer during the war, teaching radiology to other nurses and doctors on the war front and helping her mother operate mobile X-ray units for locating shrapnel in the bodies of wounded soldiers so their wounds could be diagnosed and treated correctly. As nurse radiographers, both Marie and Irène were exposed to large amounts of radiation, leading to both of them eventually dying from the consequences of such toxic exposure.

After the war ended, Irène completed her graduation degree in mathematics and physics at the Sorbonne. Now aged 21, she became her mother’s laboratory assistant at the Radium Institute founded by her. Here, she earned the nickname “crown princess” perhaps partly because many were jealous of her privileged position as the daughter of the Director of the Institute. Others felt intimidated by her in-depth knowledge of physics and mathematics, her robust physique, and her forthright way of interacting with others without bothering about ladylike mannerisms.

Following in the footsteps of Marie and Pierre, the Joliot-Curies too refused to patent their work deciding to make it freely available to the global scientific community. However, fears of their research being misused for military purposes, made them place all their documentation on nuclear fission in the vaults of the French Academy of Sciences in 1939, where it remained till 1949.

Soul mates, life partners, and fellow Nobel Laureates

Irène earned her doctoral degree in 1925, her thesis focusing on the alpha particles emitted by polonium, the element her parents had discovered. Soon after, on the recommendation of Paul Langevin, who was Irène’s major doctoral professor at the Sorbonne University, Marie hired Frédéric Joliot as her new assistant at the Radium Institute. Joliot was a first-class engineering graduate who had accepted a research scholarship.

In the beginning, Irène trained Frédéric in laboratory techniques required for radiochemical research. But gradually, the two of them discovered their many shared interests that besides science, included sports, humanism, the arts, and similar political views as well. Realising they had found their soul mates in each other, they got married a year later in October 1926. Irène was then 29 and Fred 27. Soon after marriage, they adopted the surname Joliot-Curie, though they often signed their scientific papers as Irène Curie and Frédéric Joliot.

Speaking about Irène, Frédéric said that though some regarded her as “a block of ice”, he had found in her “an extraordinary person, sensitive and poetic, who in many things gave the impression of being a living replica of what her father had been.” He had added that in Pierre’s daughter, he had discovered the “same purity, his good sense, and humility” that he had read about.

Achievements and Recognitions

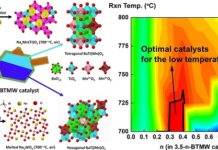

From 1928 onwards, Irène and Frédéric collaborated on carrying out research on atomic nuclei. Till then, scientists knew that a nucleus could be split into stable parts when bombarded with a powerful enough particle. Notwithstanding their failure to correctly identify the positron and neutron that they had detected, what they ultimately discovered proved to be ground-breaking.

In 1934, when the Joliot-Curies bombarded a thin piece of aluminium with alpha particles, they discovered an unknown kind of radiation that persisted even after the source of radiation was removed. They found this was because aluminium atoms had been changed into a radioactive isotope of phosphorus. That is, by irradiating a natural, stable isotope of aluminium, they had artificially created a radioactive element – an unstable isotope of phosphorous. They found they could also similarly create radioactive isotopes of nitrogen from boron, and of silicon from magnesium. Their amazing discovery rightly won them the Nobel Prize the following year and resulted in further research on the fission of heavy metals, impacting the fields of chemistry, medicine, and biology.

Irène and Frédéric’s work on artificially synthesized, radioactive isotopes forms the basis of a lot of biomedical research and cancer treatment methods today like for example the use of radioactive iodine therapy for thyroid cancer. Their pioneering work also led to the discovery of the fission of uranium and the creation of powerful weapons of war.

The Nobel Prize got Irène Joliot-Curie a professorship at the Sorbonne’s Faculty of Science, while Frédéric was appointed as a Professor at the College of France. In 1936, the French Government appointed Irène as Undersecretary of State for Scientific Research, following which she helped in founding the National Centre of Scientific Research. In 1946, she became the Director of her mother’s Radium Institute.

Besides scientific work, Irène was also actively involved in social and political movements including the Suffragette movement. She was a member of the National Committee of the Union of French Women and the World Peace Council and actively supported the education and intellectual advancement of women. She and her husband were also made officials of the French Legion of Honour. Besides, Irène was a member of many international academies and scientific societies and was conferred with honorary doctor’s degrees by several universities.

Following in the footsteps of Marie and Pierre, the Joliot-Curies too refused to patent their work deciding to make it freely available to the global scientific community. However, fears of their research being misused for military purposes, made them place all their documentation on nuclear fission in the vaults of the French Academy of Sciences in 1939, where it remained till 1949.

Irène and Frédéric have been honoured by having the Royal Society of Chemistry’s annual Joliot-Curie Conference on diversity in science named after them. In 1991, the Joliot-Curie crater on Venus was named after Irène. The crater Joliot on the moon is named after Frédéric.

Also, the Sorbonne University honored Irène by introducing the annual Irène Joliot-Curie Prize awarded to a noteworthy “Woman Scientist of the Year”.

Finally, after years of exposure to radioactive materials, Irène Joliot-Curie succumbed to leukaemia like her mother and breathed her last at the Curie Hospital in Paris on 17 March 1956 at the age of 58. Two years later, Frédéric too passed away in Paris on 14 August, also at the age of 58.

Paying a tribute to Irène and Frédéric, the Nobel Prize Committee in its presentation speech in 1935 had mentioned: “The results of your researches are of capital importance for pure science, but in addition, physiologists, doctors, and the whole of suffering humanity hope to gain from your discoveries, remedies of inestimable value.” That has been proved to be no exaggeration.

References

- Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014: Irène Joliot-Curie – Biographical – https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1935/joliot-curie-bio.html

- Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014: Irène Joliot-Curie – Facts – https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1935/joliot-curie-facts.html

- Famous Scientists: Irène Joliot-Curie – https://www.famousscientists.org/irene-joliot-curie/

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frederic-and-Irene-Joliot-Curie

- Sarah-Jane Cousins: Irène Joliot-Curie – 175 Faces of Chemistry, June 2014, http://www.rsc.org/diversity/175-faces/all-faces/irene-joliot-curie

- Science History Institute: Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot – https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/irene-joliot-curie-and-frederic-joliot

- Penny J. Gilmer: A Nobel Laureate in Artificial Radioactivity – Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Madame Marie Sklodowska Curie’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chiu, M. H., Gilmer, P. J., Treagust, D. F. (Eds.), Springer, 2011