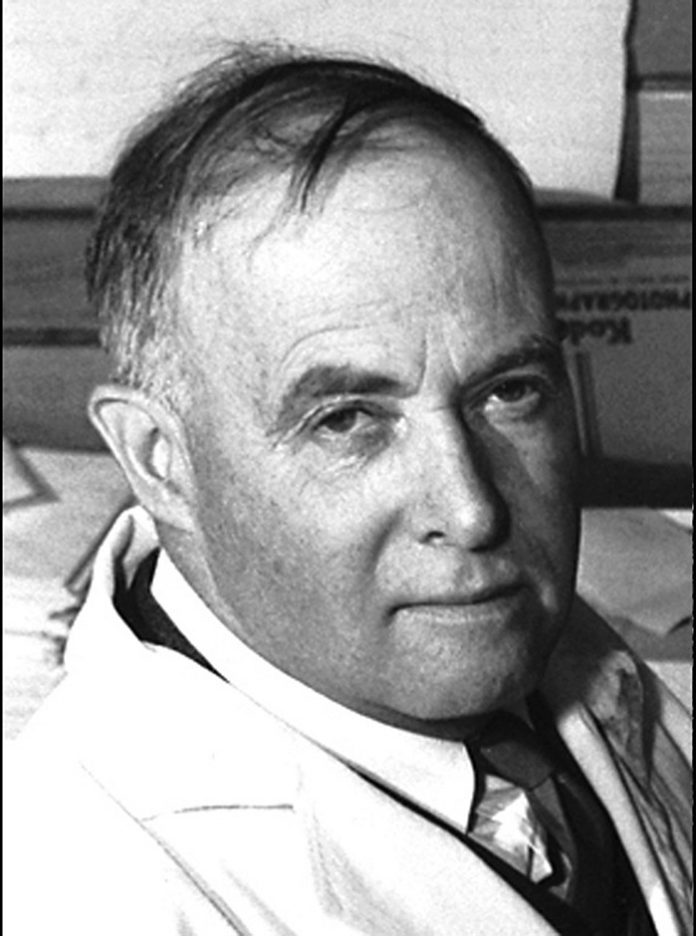

In 1917, when the pioneering American biochemist James Batcheller Sumner commenced his quest to isolate an enzyme, he had to grapple with a busy teaching schedule and yet make time for research. To make things even more difficult, he didn’t have much financial or technical support. And what was even more remarkable about Sumner’s research project was that he was attempting a feat that more experienced and well-known biochemists had failed to achieve till then.

At that time, the word ‘enzyme’ was barely fifty years old, and while scientists were familiar with enzyme-catalysed fermentations, the nature of the enzyme ferments still remained a mystery. In fact, it was believed that enzymes belonged to an as yet unknown category of chemical compounds and that it could be impossible to actually crystallise them.

When Sumner finally succeeded in his quest in 1926, he was still just an assistant professor at America’s Cornell University. By successfully isolating and crystallising urease – the enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia – he proved the experts of his time wrong. Not just that, he went on to show that most enzymes were in fact proteins.

In 1946, Sumner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for proving that enzymes can be crystallised. During his Nobel lecture, by way of explaining what had made him take up something that was considered unachievable for his research program, he said, “I desired to accomplish something of real importance. In other words, I decided to take ‘a long shot’. A number of persons advised me that my attempt to isolate an enzyme was foolish, but this advice made me feel all the more certain that, if successful, the quest would be worthwhile.”

Early life

James Batcheller Sumner was born at Canton, Massachusetts, on 19 November, 1887 into a prosperous family of cotton textile manufacturers. While in school, the only subjects he didn’t find boring were physics and chemistry. As a teenager, he was especially interested in fire-arms and often went hunting with his friends. One afternoon, while hunting grouse at the age of seventeen, his companion accidentally shot him in the left arm. Consequently, his arm had to be amputated close to the elbow.

Unfortunately, Sumner had been left-handed. After the accident, he courageously began to learn to do things with his right hand. Undeterred by the loss of his arm, he took part in athletic sports and also continued hunting, revealing how spunky and persevering he was even at that young age. Later, as a one-armed researcher, he trained himself to handle all kinds of laboratory equipment from small test tubes to bigger items with one hand. He excelled in tennis, skiing, and skating and even went on to win the Cornell Faculty Tennis Club prize. While in Stockholm to receive his Nobel prize, he had an opportunity to meet King Gustav. When the king asked him how he managed to handle both ball and racket while serving in a game of tennis, he readily gave him a demonstration.

Sumner obtained his bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1910 from Harvard College. After a brief stint at his uncle’s cotton knitting factory and a year of teaching chemistry at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, he returned to Harvard to pursue his Ph.D., studying biochemistry with Professor Otto Folin. When Folin interviewed Sumner, he had advised him to take up law instead, because “a one-armed man could never make it in chemistry”. But, true to character, Sumner took this remark as a challenge and persisted with working on his thesis with Folin. Finally, he earned his doctorate in 1914 for his thesis on “The Formation of Urea in the Animal Body”, and Folin’s admiration as well.

In the summer of 1914, he accepted an offer as Assistant Professor of Biochemistry at the Cornell Medical School, at Ithaca, N.Y.

From stiff opposition to wide acclaim for breakthrough research

In 1917, Sumner began his research on enzymes at Cornell, choosing to work with jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis) that seemed to be extraordinarily rich in urease. He thought isolating the enzyme in the pure form from this bean would not be difficult. Ultimately, it took him nine years to succeed in this task.

Sumner’s early attempts met with failure. But, neither the disappointment of failure nor discouragement from his colleagues, who thought he was attempting the impossible, could stop him from continuing with his work. He was confident he was on the right track. In 1921, on being granted an American-Belgian fellowship, he decided to go to Brussels to work with Jean Effront who had authored a number of books on enzymes. But, with the Belgian biochemist considering the very idea of isolating urease as absurd, Sumner had to give up on his plans of working with him. He resumed his work in Ithaca with even more determination, and finally succeeded in 1926. Referring to that exciting moment in his life, Sumner wrote in an autobiographical note, “I went to the telephone and told my wife that I had crystallized the first enzyme.”

However, most biochemists refused to take note of his achievement. Many disbelieved his claim of having isolated and crystallised urease. Sumner provided ample experimental evidence to show that the globulin he had isolated from jack bean meal was identical with the enzyme urease and that the enzyme was a protein. But the research papers he published were either rejected or ignored by enzyme experts, with many insisting that the protein he had crystallised was the carrier for the enzyme and not the pure enzyme.

Sumner’s strongest critics included the leading enzyme chemist of the time, Richard Willstätter, and his students in Germany who, even after several years of intensive research had failed to isolate a pure enzyme and therefore concluded that pure enzymes couldn’t be proteins. But scepticism from the European biochemists only strengthened Sumner’s resolve to defend his findings. He responded to their negative reactions by publishing ten more papers and offering additional data over the next five years. By 1936, he had twenty published research papers on urease to his name.

Luckily for Sumner, notwithstanding the opposition from prominent biochemists, his research work was appreciated at Cornell and resulted in him being offered a full professorship at the University in 1929.

In 1930, once again it was proved that Willstätter was wrong and Sumner was right when John H. Northrop of the Rockefeller Institute also showed that enzymes were proteins and reported the crystallisation of pepsin and other enzymes. In 1937, Sumner succeeded in isolating and crystallising a second enzyme, catalase, present in blood. That same year, more recognition of his work came by way of a Guggenheim Fellowship being awarded to him, following which he spent five months in Sweden working with the famed Professor Theodor Svedberg. Soon afterwards, he was given the Scheele Award in Stockholm.

A lifetime devoted to enzyme chemistry

By now it was acknowledged that Sumner had developed a general crystallisation method for enzymes. But the crowning acknowledgement was being picked as one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1946 “for his discovery that enzymes can be crystallized”. The other co-winners of the Chemistry Nobel Prize that year were Northrop and Wendell M. Stanley, who won it “for their preparation of enzymes and virus proteins in pure form”.

In 1948, Sumner was elected to the National Academy of Sciences (USA). In 1949, he was elected as a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Sumner spent his entire career at Cornell in Ithaca, and went on to become a pioneer in biochemistry there. In 1947, one year after he got the Nobel Prize, he was appointed as the director of the enzyme chemistry laboratory at the University’s College of Agriculture.

Soon after his retirement from Cornell in July 1955, Sumner was planning to travel to Brazil for organising a research program on enzymes at the University of Minas Gerais, when he suddenly took ill. He was diagnosed with cancer and died just a month later on 12 August, 1955 at a hospital in Buffalo, NY.

James Sumner’s pathbreaking work paved the way for further research on the chemical structure of pure enzymes and resulted in the study of enzymes playing a key role in research in modern biochemistry.

References

1. Nobelprize.org: James B. Sumner – Biographical – Nobel Media AB 2019, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1946/sumner/biographical/

2. James B. Sumner: The chemical nature of enzymes – Nobel Lecture, 12 December 1946, https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/sumner-lecture.pdf

3. Soylent Communications: James B. Sumner – http://www.nndb.com/people/476/000100176/

4. Leonard A. Maynard: James Batcheller Sumner – National Academy of Sciences, 1958, http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/sumner-james.pdf

5. Robert D. Simoni, Robert L. Hill, Martha Vaughan: Urease, the First Crystalline Enzyme and the Proof That Enzymes Are Proteins: the Work of James B. Sumner – J. Biol. Chem. 69, 435–441, J. Biol. Chem. 98, 543–552

6. The FamousPeople.com: James B. Sumner Biography – https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/james-b-sumner-7281.php

7. James K. Laylin: 1946 Nobel Laureate James Sumner 1887-1955 – Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, 1901-1992.