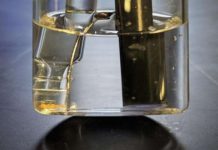

Mercury, the only metal that is a liquid at room temperature, has fascinated people right from ancient civilisations and alchemists to the scientists of modern times.

One of the transition elements of the periodic table, the silvery metal, also called quicksilver in English, was originally called hydrargyrum, a Latinised form of a Greek word meaning ‘water-silver’. It’s chemical symbol Hg has been derived from this name. With atomic number 80, mercury is a very heavy metal. A one-pint beer mug of it would weigh around 8 kilos. Imagine the strain of lifting that with one hand!

Mercury is also a rare metal, occurring in the earth’s crust at an average concentration of around 0.08 g per ton of rock. It is found in the elemental form in very small quantities. Its most abundant ore, the red mercuric sulphide – cinnabar – has been used for extracting mercury and for various other purposes across the world for millennia. From ancient times, people have been condensing the vapours emitted on heating cinnabar to obtain pure mercury.

The ‘First Matter’

Mercury was given its present name by 6th century alchemists. Like Islamic alchemists, European alchemists too believed mercury was the ‘First Matter’ and that it was present in all other metals. Mercury was fundamental to the art of alchemy which itself led to the establishment of the philosophical tradition on which the principles of the scientific method are based.

Alchemists believed that mercury when combined with other base metals in the right proportions could be transmuted into gold. We now know that is not true. But, perhaps the basis of what the alchemists believed was mercury’s ability to combine with a noble metal like gold, something that was known even to ancient civilisations. Down the ages, man has exploited mercury’s remarkable property of dissolving gold and silver and forming amalgams with them to extract these precious metals from alluvial river sediments and mines. (They separated the dissolved gold or silver from the amalgams that were formed by distilling off the mercury.) For instance, the Spanish conquerors used mercury obtained from the huge cinnabar deposits in the mines of Huancavelica, Peru, for extracting silver from silver mines in South America. Similarly, during the well-known California gold rush of the 19th century, miners used mercury obtained from cinnabar to extract gold from river sediments.

Other historic and traditional uses

The Chinese used cinnabar, the naturally occurring mineral of mercury, in different medicines, and as a pigment for imparting a bright red colour to lacquer and ceramics. Referred to in ancient Indian literature as rasasindur, cinnabar was used in ayurvedic medicines.

The Romans used it as a pigment in paintings and in rouge-like cosmetics for colouring cheeks. The ancient Greeks were known to use it in ointments for healing wounds. Its use can even be seen in Neolithic-Age (around 10,000 to 3000 BC) cave paintings. During the Middle Ages, cinnabar was mixed with the wax used for seals stamped on formal and official documents.

Large quantities of liquid mercury have been discovered in Egyptian tombs. In Islamic Spain (8th-15th century AD), sizable reflecting pools filled with mercury served as mirrors in which Caliphs could gaze at their reflections. Many castles of that period were even known to have mercury fountains.

Liquid mercury’s unique property of not wetting or sticking to glass, together with its rapid and uniform volume expansion, made it ideal for thermometers, thus resulting in it playing a crucial role in the Scientific Revolution that got underway in Europe around the 16th century. Today, we have digital thermometers, but they are not as accurate as the mercury ones that are still used in many homes. Barometers and manometers exploit two of mercury’s other properties – its high density and low vapour pressure.

Many may remember the old antiseptic of choice used in homes for curing cuts and bruises – mercurochrome – a tincture that stained the skin red and contained a small quantity of a mercury compound. Also, dental amalgam fillings containing around 50% of elemental mercury by weight are in use since around 150 years. Some modern day uses include electrical switches, high-pressure mercury-vapour lamps, compact fluorescent lights, industrial fungicides, and electrolytic cells and catalysts for chemical manufacturing.

Unfortunately, this useful and amazingly lustrous metal also has a dark and dangerous side.

A two-faced metal

Notwithstanding the fact that the use of mercury and its compounds has been closely linked to human history for long, the fact is that mercury is highly toxic. In fact, it is the most poisonous non-radioactive element on earth. Like lead, mercury is a deadly neuro-toxin. It affects the cerebellum, the part of the brain that co-ordinates our movements and the neurological damage it causes is irreversible. Besides, it damages the kidneys and other vital organs too.

The major mercury compounds include: mercurous chloride or calomel – prescribed till recently as a laxative and diuretic and as a cure for syphilis, and added to teething powders for babies, the mercury poisoning in these tiny tots showing up as the ‘pink disease’ that caused an unnaturally bright pink colouration of their fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, and buttocks; mercuric chloride or corrosive sublimate – a poisonous chemical used as a disinfectant; and mercuric sulphide or vermillion (present in the ore cinnabar) – a less poisonous compound mainly used as a paint pigment.

In the 19th century, hatters in the hat industry ended up suffering from ‘hatter’s shakes’ and ‘mercury madness’ due to their handling of another mercury compound – mercuric nitrate – for soaking the pelts of rabbits and beavers and turning them into felt for making hats. The peculiar condition that afflicted these industrial workers gave rise to the phrase ‘mad as a hatter’, as also the name of the well-known character in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland – the Hatter, popularly called the Mad Hatter, being referred to in the book as mad.

Mercury poisoning though rare today, claimed many more lives in the past, even the Romans and Greeks being aware of its toxicity. From around the 16th to 19th centuries when metallic mercury and calomel were used for treating syphilis, a large number of people died of slow mercury poisoning.

Till a few decades ago, teachers too were known to encourage their students to check out the cold, clammy liquid mercury in school labs. Alarming though that may seem, the reassuring fact however is that more than metallic mercury that is poorly absorbed through touch, it is the vapours emitted by it that are extremely poisonous.

Around half the quantity of mercury vapours entering our environment comes from volcanic eruptions and other geological occurrences – processes over which we have no control. But the other half is a result of human activities.

Of this, the mercury vapour arising from accidentally smashed fluorescent bulbs, broken thermometers, or improperly discarded dental fillings account for a tiny fraction of the 2000 or so tonnes of mercury released by humans into the atmosphere each year. Around a quarter of the atmospheric mercury comes from power generation when coal, a fuel that contains traces of mercury, is burnt. Gold mining is another cause of mercury emissions.

Also, while almost all compounds of mercury are toxic, the most lethal of them all is methyl mercury, an organic form of the metal that harms the central nervous system, even causing foetal deformities. It is a deadly pollutant in rivers and lakes. When mercury-containing industrial wastes are dumped into water bodies, anaerobic microbes convert inorganic mercury into methyl mercury that ultimately makes its way into the bodies of fish. People who eat such contaminated sea food become victims of mercury poisoning.

Introduction of safety regulations

Thankfully, in the last few decades, a number of safety regulations and modifications in industrial processes related to mercury have been introduced. The emphasis is now on safer processes for extracting mercury. The newer methods involve dissolving cinnabar in solutions of sodium hypochlorite or sulphide, and then recovering mercury by precipitation with zinc or aluminium or through electrolysis. Also, plants that use cinnabar for manufacturing sodium hydroxide and chlorine by electrolysis of brine are expected to be phased out by 2020. Similarly, other uses of mercury that are being gradually phased out or are on their way out include its use in felt production, and in the manufacture of batteries, fluorescent lights, thermometers, barometers, and medicines.

Special equipment is being installed in power stations, cinnabar smelters, gold refineries, and cement works for trapping and collecting the mercury vapours emitted. In 2013, over 90 countries signed the UN’s Minamata Treaty whose objective is to impose controls and reductions on a range of products, processes, and industries where mercury is used, released or emitted.

What can you do at the individual level? Make sure inoperative or broken domestic products containing mercury are disposed of safely, remembering to use some common-sense measures as well. For example, ensuring you’re not wearing any gold jewellery while handling spilled mercury. That just might prove to be too costly!

References

- WebElements: Mercury: historical information – https://www.webelements.com/mercury/history.html

- Royal Society of Chemistry: Periodic Table: Mercury – http://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/80/mercury

- Anne Marie Helmenstine, Ph.D.: 10 Mercury Facts (Element) – ThoughtCo., 3 April, 2018, https://www.thoughtco.com/mercury-element-facts-608433

- K. Kris Hirst: Cinnabar – The Ancient Pigment of Mercury – ThoughtCo., 8 February, 2017, https://www.thoughtco.com/cinnabar-the-ancient-pigment-of-mercury-170556

- John Emsley: Mercury – Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements, Oxford University Press, 2001

- Dr. Doug Stewart: Mercury Elements Facts – https://www.chemicool.com/elements/mercury.html

- Joel D. Blum: Mesmerized by mercury – Nature Chemistry, 21 November, 2013 online, https://www.nature.com/articles/nchem.1803

- Justin Rowlatt: Mercury: A beautiful but poisonous metal – BBC News Magazine, 30 November, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25130770

- Julie Sloane: Mercury: Element of the Ancients – Dartmouth Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program, 26 July, 2016, https://www.dartmouth.edu/~toxmetal/mercury/history.html.